‘Invisible Creatives’ looks at the position of freelancers, and sole traders, in the light of Covid-19 impacts. These creatives make up, with micro-companies (less than four people), over 90% of the creative industries, which contributed over £115bn gross value added to the UK economy prior to the pandemic. A figure which has been pointed out by the Creative Industries Federation(CIF) was greater than automotive, aerospace,life sciences and oil and gas industries combined. The question is what has happened to the individual creatives who support this vast sector, and why have they been so invisible in public debate?

Freelancers, sole traders, and directors of Micro-Companies.

Very early on in the pandemic people pointed out that many freelancers, etc. were missing out on government support. Even after the March 2021 budget the Resolution Foundation stated that the Government had failed to cover 1.5 million of the UK’s previously 5 million-strong army of self-employed workers.

The impact in the performing arts sector on the income of backstage staff, performers, and musicians has been highlighted in such initiatives as ‘The Show Must go On‘ to BECTU’s ‘New Deal for Freelancers‘. Hardships funds have been set up in Scotland, and Wales, while national bodies e.g. Arts Council England and major charities e.g. Genesis have changed their policies to reflect the problems being faced by people working in the creative sector.

A Different Future

Despite all these various activities a report published in Feb 2021 found freelancers were 20% more likely than organisations to have seen a drop in income of 75% or more since the pandemic began. The result has seen a significant drop in self-employed workers, many in the hardest hit parts of the economy. The Resolution Foundation study shows around 700,000 self employed have stopped working entirely during the current restrictions, up from 460,000 in May 2020.

By the end of 2020 The Centre for Cultural Value using ONS statistics showed that the number of freelancers working in creative occupations was lower (around 156,000) than the beginning of 2018 (around 176,000). A substantial reversal of the upward trend of previous years.

In a global survey of creatives by Genero, looking forward –

“The overwhelming majority would like to freelance (47 per cent) or work as a partner in an independent creative business (35 per cent), accelerating a shift to independent, flexible work.”

This points to the increased need for flexibility in the workforce, the discovery of not only working from home but working digitally provides real economic benefits and the acquisition of new skills during the pandemic. With online learning/skills development bound to increase and digital delivery for many creatives areas becoming the norm the ‘invisible creatives’ are not going away. Another factor is the under counting of many creatives, which we explore later in this blog.

So why are they invisible?

The simple answer is individuals and micro-companies are not seen as an industry.

Compared with a car plant with its 2000 workers in one place, or 5,000 working at steel plants individual creatives employment does not catch the headlines, because it is scattered across the UK in small personal enterprises and studios. Does this matter?

Compared with a car plant with its 2000 workers in one place, or 5,000 working at steel plants individual creatives employment does not catch the headlines, because it is scattered across the UK in small personal enterprises and studios. Does this matter?

Well the failure of the government to have the capacity to respond to the freelance and sole trader crisis during the pandemic has highlighted one problem with this perspective. However, given the scale of the contribution creatives make to the UK economy, and the ongoing decline in traditional manufacturing there is clearly an argument for paying them some more attention.

The difficulty is how?

Dealing with a diverse set of working practices from theatres and museums, games designers and film crews to architects, fashion designers and visual artists can appear too difficult to organise. One cornerstone of current government engagement is the Creative Industries Council. However, this is dominated by large creative organisations ranging from publishing houses to the BBC. Bodies which employ ten of thousands of freelancers and micro-companies but cannot realistically be said to represent them.

With respect to this situation a collective demand from the various freelancer and sole trader organisations for the setting up of a a Creators Council was called for again in 2020. Such a body representing creators from musicians to writers, from actors to directors would at least give a voice to this diverse community at a national level.

Beyond a National Voice.

In 2018 the Creative Industries Sector Deal was launched as part of a National Industrial Strategy. A Strategy which has been abandoned in March 2021. However, the ramifications of the strategy and some lessons to be learnt from it will be with us for some time. At the heart of of the deal was the concept of Creative Clusters, based largely on NESTA research and implemented via the AHRC’s Creative Clusters and Audiences of the Future programmes.

Creatives Cluster were defined as largely ‘Travel to Work Areas’ (TTWA) with a significant percentage of creative companies. Inevitably, this focused on the larger metropolitan areas in the main. However, the decisions to back creative cluster projects, which gave the vast majority of the funding (£110m) to Universities saw partnerships with the BBC, Heathrow Airport, Burberry, V&A, N.I. Screen, NFTS, and various other national bodies. In addition, over 90% of the funding remaining within Universities’ control. The option to support direct funding to freelance groups and micro-companies was on the table but rejected. Indirect funding has been achieved in some instances but the failure to engage with the vast majority of the sector directly was a missed opportunity.

The question is why was this opportunity missed?

It would be easy to point to the politics of national funding. This involves providing funds across all regions/nations regardless of the quality of proposals, but more significantly the perception that bigger is better, as a presentation to government Departments and Ministers. It is easier to justify that you are working with the BBC, etc. than hundreds of freelance creatives who no-one has heard of! So inevitably when national funds are offered to the creatives industries they end up with national bodies, and the majority of the sector is left competing for ‘hand outs’.

Micro-Clusters

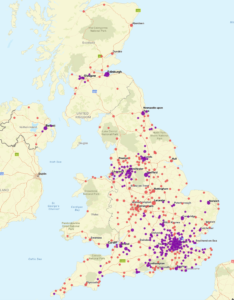

However, there is another level of invisibility to this whole question. This was highlighted in the Policy and Evidence Centre’s(PEC) report in November 2020 on ‘Creative Micro-clusters’. This web scrapping exercise reached beyond the TTWAs and sought out smaller groups of creatives/companies. The result were maps which showed creative enterprise were far more evenly distributed across the UK, than the original creative cluster work highlighted.

Here is the map showing the distribution of creative micro-clusters across the UK.

The purple dots show micro-clusters within existing the large creative clusters. The red dots highlight those outside these defined area. This web-based exercise illustrates the wide spread of creative enterprise across the UK. Note: you may miss the two red dots in Shetland and Orkney in this standard display, but they are there. Each red dot equates to fifty creative companies/enterprises in an area. However, BCre8ive’s research in Northern Devon, shown as two red dots on the map, illustrates just how far off the mark this approach is.

The Really Invisible

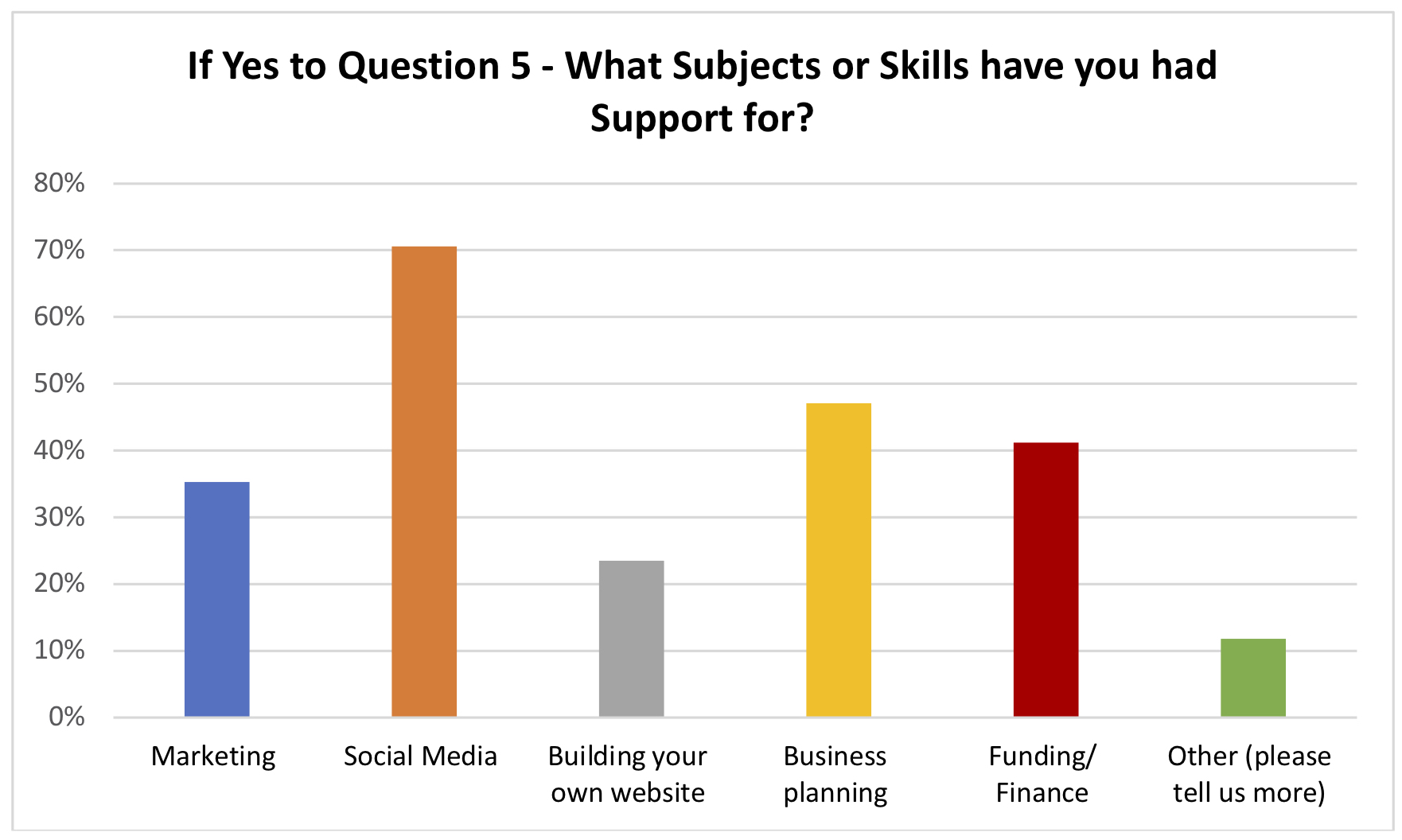

Web scrapping in this instance required a website with an address attached. A recent survey of local artists and makers in Northern Devon revealed over 30% did not have a website, in addition several did not have their address attached to their website. The more focused qualitative research revealed there are over 300 active artists and makers in the area. Three times the number suggested by the micro-cluster exercise. It is probable that this scale of invisible creatives can be found across the UK.

In addition, previous research by PEC discovered that visual arts and craft micro-clusters in very rural areas were more likely to be ambitious and have higher growth than those located in the major cities and towns. While, the Crafts Council report stated craft objects sold in England alone more than tripled over the course of the last 13 years, going from £883 million in 2006 to over £3 billion in 2019.

Though this research focused on these two creative groups it does not take much to realise that a similar scenario applies to nearly all writers, designers, illustrators, directors, performers, etc. i.e. the vast majority of creatives in the UK. It is also worth noting the extent Grayson Perry’s Art Club highlighted the range and degree of invisible creativity in the UK, beyond traditional industrial models, which none the less could be part of a larger productivity, and economic expansion.

Moving On

The implications from these different levels of ‘invisibility’ with the UK’s approach to supporting the creative industries means it will largely fail in its ambition to boost productivity, economic growth, and inclusion. Working with so many individuals and micr0-companies will never be easy but it is not impossible.

- Moving away from national bodies and engaging directly with creators will ensure they do not remain invisible in the regional and national systems.

- Creating online locally focussed support services targetted at particular creative activities will overcome the top down, generic, approach which is undermining this sector’s growth.

- Creating new financial pathways adapted to small enterprises and sole traders will ensure growth across the UK.

- Including the majority of the sector in all governmental promotional activity will open up the chances for substantial exports.

It is perhaps worth remembering at this point that the Unesco Global Cultural Times report revealed that the visual arts sales were worth more globally than music, film, advertising and newspaper/magazines. They were second only to television. A major source of global revenue created by invisible creatives!

The UK film industry exported a record

The UK film industry exported a record

The UK publishing industry has also been negatively affected by digital disruption. The impact of Amazon on

The UK publishing industry has also been negatively affected by digital disruption. The impact of Amazon on  A New Digital Structure

A New Digital Structure Access to Finance

Access to Finance

A New Creative Conversation

A New Creative Conversation The first statement from most creatives with respect to content development is “We do not have time for our own development”. Trapped in a commissioning merry-go-round freelancers and micro companies have little or no time to undertake original content development outside their commissions. However, development takes time, and commitment.

The first statement from most creatives with respect to content development is “We do not have time for our own development”. Trapped in a commissioning merry-go-round freelancers and micro companies have little or no time to undertake original content development outside their commissions. However, development takes time, and commitment. The Class Barrier

The Class Barrier The second area identified was Internships and free working, which have become a standard part of entering much of the creative industries. For working class individuals who do not have the financial support available to those from upper-class and middle-class backgrounds this option is limited, if not impossible to take up. Furthermore, it is compounded by the informal networks by which many, if not most, of these internships are set up. As the majority of posts are never advertised, new entrants who are not already part of an established network are automatically denied access.

The second area identified was Internships and free working, which have become a standard part of entering much of the creative industries. For working class individuals who do not have the financial support available to those from upper-class and middle-class backgrounds this option is limited, if not impossible to take up. Furthermore, it is compounded by the informal networks by which many, if not most, of these internships are set up. As the majority of posts are never advertised, new entrants who are not already part of an established network are automatically denied access.

A major solution to the latter point and a substantial means of supporting the diversity of freelancers and micro-companies would be the creation of a UK wide digital support network, as outlined in BCre8ive’s ‘

A major solution to the latter point and a substantial means of supporting the diversity of freelancers and micro-companies would be the creation of a UK wide digital support network, as outlined in BCre8ive’s ‘

elbegzaya

elbegzaya