This guest blog is written (31st may 2015) by Tanya Nash, a BCre8ive Mentor, and relates her experience of attending an immersive theatre experience and this use of a dramatic world.

On Wednesday, I was offered a ticket to see a play at The Young Vic theatre, World Factory by METIS that I knew nothing about. The theatre’s website told me,

“From the factory floor to the catwalk, from Shanghai to London, World Factory weaves together stories of people connected by the global textile industry.”

I wondered if I was in for a sad and depressing afternoon.

Walking into the studio theatre, the first thing I noticed was that there was no stage. The room was full of small oblong tables, each with a single work lamp. And I had to sit at one of them. I felt nervous and wondered what was going to happen.

There were 4 actors who were both our narrators and game tutors. And then I realised that I was about to experience my first piece of immersive theatre. As audience members our role was to make managerial decisions on the running of a garment factory in China.

Before the game began we were given an introductory account of the history of textile making in both the UK and China via actors, video clips and photographs projected onto all four walls around us. Then we were asked to open the cardboard box on our table in front of us.

Opening the Box

Whilst we were doing this, we quickly realised that we also needed to introduce ourselves and find out our skill set in the real world, if we were going to be at all successful. We were six confident women, ageing from 40s – 70s with a similar political outlook. But this would obviously not be the case for all the groups.

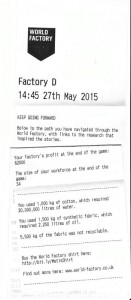

Inside our box were a number of items; a wad of play money, a folder containing the photographs and names of our 24 employees and a leaflet giving us more details about the world we were now in. The game began when our game tutor handed us our first scenario card. And on the back of the card were 2 choices. Once we had made our decision we scanned that choice via the correct bar code. And our tutor gave us the next card.

“Humans had built a world inside the world, which reflected it in pretty much the same way as a drop of water reflected the landscape. And yet … and yet … ” Terry Prachett in Wyrd Sisiters

As the game unfolded we made many decisions. Would we cut staff or lower wages to survive? Would be take a grant to improve working conditions? Would we make a new product? Would we allow workers to unionise? Would we break the law? Would be provide them with transport back to their home town for their annual Spring break? And we were presented with garments we had made, new members of staff and also offered bribes.

It wasn’t always easy to predict an outcome. For example, we chose the option to install better heating for our workers. But instead of improving productivity, our workers suffered from heat exhaustion.

The End Game

At the end of the one-year story period (60 mins in real time), our role was over. Now we discovered why we had had to scan our decisions via their bar codes. All the statistics from the 20 groups (120 audience members) participating were screened onto the walls around us. Not surprisingly, the groups that treated their workers poorly made the most money. And the opposite decision was also true. My group was a middle of the road team who played it safe, did our best for our workers and we survived. In fact no team went bust which surprised me. But this wasn’t the end of the show. There was one more choice to make.

Each of the 4 actors had a minute to ask us where we wanted to invest our profits – textile recycling, new markets in Africa, improving working conditions for Chinese workers or investing in UK garment trade. We put our money into re-cycling, as did most of the room.

Using Dramatic Worlds

My background is in the creation, development and production of drama series for both radio and television. Drama series require fixed narratives and hook their audiences via great characters and interesting story outcomes.

World Factory was a fascinating insight into another way of using a dramatic world. Characterisation was minimal and provided by printed biographies and still photos of our key players in China. The narrative was driven by our choices based on exposition rather than character or story. The dramatic conflict was provided by the audience negotiating with each other and our games tutor.

To prevent us being overloaded with detail, there were times when we lacked enough information to properly inform our decision. And we were a team who were all of similar mind. It would be fascinating to see the show again with people who thought quite differently to me.

A Mentor’s Perspective

Looking at this from the perspective of a BCre8ive mentor, I can see other possibilities for this dramatic world such as online gaming, a graphic novel or short web series. And one of my friends thought it would be a good training experience for his team in the corporate world.