Sources of Inspiration

On Quora this week someone wrote they had a great film idea, and just needed someone else to write it up! The problem, as one reply noted, is everyone has at least one great idea for a film, but not everyone turns that idea into a film, a novel, a play, a painting, photograph, song, illustration, or animation.

The truth is most ideas are not really solid ideas, but sources of inspiration, a starting point on a creative journey, which may or may not be successful, and/or rewarding.

This blog is about the possible sources of inspiration for those who want to have more than one idea. It is a simple list of the main sources, along with a few guidelines on how to use them, and the pitfalls to avoid.

Try a few out, enjoy the process, and then you will not be left wondering if you have only one great idea.

1. Adaptation

Adaptation involves changing the medium being used from one form to another. Novels and short stories continue to be the source of the majority of adaptations for film and TV. However, comic books, video games, cartoons, poetry, biographies, songs, and graphic novels have all been used on more than one occasion to produce works inn other mediums.

The most important things to discover before you embark on an adaptation is, ‘Who owns the rights?’ and, ‘Are they available for adaptation?’ Undertaking an adaptation without clearing the rights has proven to be a very frustrating experience for many new writers. It can also prove very expensive for producers.

The process of creating an adaption is the same as if you were starting with an original idea. Many adapters have said that you have to start afresh, creating an original work using the original source as research material. Obviously in some cases the original is so well known, or loved, that the adaptation sticks very closely to the original but you only have to look at the new version of Sherlock Holmes stories to see how even in this sort of scenario things can be pushed a long way.

“Look you can’t be faithful to the book. Or if you’re faithful to the book, it’s only coincidental. You’ve got to be faithful to your audience.” Nunnally Johnson, screenwriter – Grapes of Wrath, The Moon is Down, the True Story of Jesse James and The Dirty Dozen.

“The first question for anyone transposing a book to the screen is, how to smash up the original and do it justice in another way” Jeanette Winterson

2. Contemporary True Stories

These stories are the basis of many television dramas, crime fiction, and feature films. The question of rights applies equally here, though instead of resting with the creators of work they rest with participants in, and in some cases, the journalists who have reported on, the events. Note: this obviously only applies to recent true stories for historical true stories see the note below.

The key issue is, ‘How much of the material you wish to use in your screenplay is in the public domain?’ The public domain is where material is available to the general public. This may be obtained from various sources including newspaper and magazine articles, court records, and some government records. (For a detailed view on how this works in your country consult a lawyer)

Many true-life stories have been used, based upon public domain material, without any permissions being granted by the people involved. However, it is advisable if you are writing about actual events to obtain a written option on people’s stories or accounts of events prior to committing to the work. In making documentaries, a waiver is normally signed by participants to ensure the documentary maker can use any material they record.

The form of an option deal or waiver can be obtained from producer’s organisations or a good media lawyer. They can also be found in standard books on film or television production or legal aspects of journalism (See ‘The Option and Purchase Agreement’ in Writing Docudrama, Alan Rosenthal, Focal Press, 1995.)

Just fictionalising a story may not protect you from being sued if you are seen to have defamed someone or invaded their privacy. The laws on these areas vary from country to country so you need to consult a lawyer to ensure you are operating within the appropriate legal framework.

Another potential problem with true stories is that lots of other writers read the same newspapers, books, etc., and create a work based on the same story.

3. Historical Events

History is everything, which happened before today: a rich source of stories.

However, if it requires contemporary locations and costumes, history is expensive to recreate. (A standard film industry estimate is that a historical setting increases the budget by a third.). Which is why so many historical narratives start off as novels, or graphic novels.

However a work set ten years ago will not generally be seen as historical as finding locations, and costumes for this period is not difficult, yet. However, setting a screen work thirty to forty years ago would prove more difficult. It would therefore generally be seen as an historical piece.

One answer to this problem may be to approach the material from a low-budget perspective e.g. in film ‘Orlando’, or, ‘l, the Worst of All’ or to work in animation or on stage, where costs can be kept down. This solution allows you the chance to see the drama realised, but requires a very distinct, and often dialogue-based, solution to the narrative problems imposed.

The issue of copyright can prove problematic for historical true stories if an author has written the definitive book on a person or event, and you have not obtained the rights to their book, you may need to undertake extensive research yourself to avoid copyright infringement issues. As with all things involving copyright it is best to seek advice – your local writers union or guild may be able to help you on this.

4. Future Events

The predicting of what might happen in the distant future has always been a source of stories for creatives. This often results in a major piece of creative work with whole worlds and peoples having to be invented e.g. ‘Star Wars’; Asimov’s ‘Robot’ series.

A significant number of science fiction works have been set in the near future: e.g. ‘Jurassic Park’, ‘Alphaville’. Or they have brought something from far away into our contemporary life: e.g. ’Invasion of the Body Snatchers’; ‘Starman’.

The same issue of cost applies here as it does to historically based work. With low-budget an option: e.g. ‘Dark Star’ or ‘Red Dwarf.

These first four sources suggest avenues for your research. They also often contain the kernel of a main story. The following sources of inspiration don’t give you quite so much.

5. Existing Screen Material

Existing works can provide ideas for new original screen works. What you are looking for in existing screen works are stories, characters or events, which act as a source for a new story, or theme, you can then explore. This stimulus doesn’t have to be another fictional narrative. It could be part of a documentary, a news item, or even another drama. Fairytales, myths and fables are also great stimulus for screen ideas (see Aronson, L, Screenwriting updated pp. 23-30).

Many creative works are designed with sequels in mind. If you receive a commission to create a sequel, another version, the problem is you will usually be required to write to someone else’s requirements. The compromises that involves may well not fit your creative inclinations, which can lead to more perspiration than inspiration!

6. Headlines

Headlines in newspapers, magazines, or journals, are short, sharp phrases, sometimes of only one word, which grab your attention. They may suggest stories, characters or situations, worth developing.

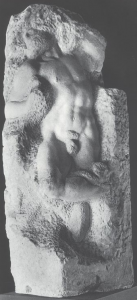

7. Visual and audio material

Given the significance of visuals in contemporary life it is hardly surprising that visual material is often a good starting point for ideas. Finding a way to randomly select images is key as then you can engage with the stimulus afresh. Going onto image libraries such as Getty Images enable you to do this .

Some writers find audio more stimulating.

In fact, all senses can be used to stimulate the imagination.

Colour and Light Inspire

8. Dreams

Many creatives have started their projects on the basis of dreams, both those remembered from sleep, and daydreams, when imaginary scenarios suddenly enter your imagination.

The trick here is to have a notebook close at hand at all times, electronic or physical, especially before going to sleep and first thing after waking up, and note down all those things you can remember.

9. The ‘What If?’ Scenario

This is one for when you are stranded at a railway station, or completely stuck for a new idea. Ask, ‘What if…’ and then add the most outrageous, funny, absurd thing that comes into your mind. Then apply it to an everyday situation or character.

The key thing with all these sources of inspiration is to treat them as a means of generating lots of ideas but realise that none of them will be good or bad at this stage. Keep the critical ‘voice’ in the back of your head gagged while you do generate ideas. There will be time later to review and develop them or reject them later.

10. Your own life

Often used phrases from established creatives, include ‘Write what you know, or Use your own life’ These phrases should view carry a major creative warning – ‘THIS DOES NOT MEAN, JUST RECREATE SOME RECENT ASPECT OF YOUR OWN LIFE’.

Anyone who has ever worked in development, read plies of unpublished work, scanned YouTube quickly realises that one of the first mistakes most people make is to create a work, based upon a series of episodic moments in their life. These outpourings generally fail dramatically, and the reason they fail is because the source material is flawed.

Life does not, in most people’s experience of it, have neat dramatic structures, nor do we understand why everyone does what they do, or even why things happen. If we did, then we would lose one the most significant appeals of creative works – its ability to provide some means of working out why some aspects of life are as they are.

In addition to this, most creatives are too emotionally involved in their own life experiences to be able to amend them or change them for the sake of a dramatic story, or character development.

Finally, we experience people from one perspective – our own. Being able to see beyond your own position is often key to creating a great work.

11. ‘Use what you know’

There are three distinct aspects of ‘use what you know’ which are fundamental to creativity and should be central to any creative’s approach to new work.

i) Knowing the nature of particular types of work.

If you want to write thriller, depict a family comedy, create an investigative documentary, or any other type of work, you need to understand the basic parameters of this particular type of work, as it is currently used, and work with them.

Far too many creatives attempt works without having grasped even the basic conventions of the type of screen work, which they claim to be creating.

ii) Knowing the emotions you are working with.

We engage with creative works, and expect to have emotional responses, as well as intellectual ones. These vary enormously from being intrigued, and surprised to being thrilled, and scared. We may smile, laugh, cry, or become angry.

However, to read most screenplays, walk around most galleries, or sit in most theatres, you would think that major emotion was the last thing the creators ever intended to engage. Instead, developing boredom or confusion in the reader/audience/viewer seems to be the major aim!

Any work can use emotion to engage a reader, or an audience. Not only emotion in terms of what the characters are experiencing but also the narrative needs to engage the audience emotionally, and keep them involved.

iii) Knowing the subject matter

One of the major criticisms of many works is that they are ‘a bit thin’. By this people mean there may well be a theme, a story and characters developing through the work, but how it is expressed is unoriginal, repetitive, or just strung out for far too long. The major reason for this is undoubtedly the lack of knowledge the creator has of the world of the work. They simply haven’t done enough research and don’t know the world well enough in order to generate the multiple ideas that are required if a work is to engage.

These eleven points are not comprehensive but I hope this overview gives you enough different approaches to begin to come up with ideas of your own.

You will still, of course, have to develop them into a great work.

ADD your own story about where you found a great idea.

To put in context it is worth watching this short interview with musician Nate Ruess. The note to take away here is to see that one person will inevitably have the beginning of a work, but the key point is that others contribute and in the end the final work results form everyone. Recognising this, and not worrying about who started. who did what, and whether your ego is more important than the project are key essentials to good collaboration. However, everyone needs to get the credit for being part of the process.

To put in context it is worth watching this short interview with musician Nate Ruess. The note to take away here is to see that one person will inevitably have the beginning of a work, but the key point is that others contribute and in the end the final work results form everyone. Recognising this, and not worrying about who started. who did what, and whether your ego is more important than the project are key essentials to good collaboration. However, everyone needs to get the credit for being part of the process.